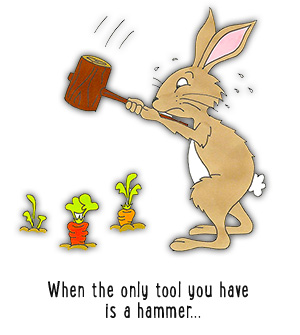

Perfectionism is a good strategy for a few things in life, but can become over-applied

Sandy sat there, vacuuming any positivity out of the atmosphere. She was, by her own admission, intolerant – because “other people are so often stupid!”

I sat across from her and concentrated on not being stupid.

“Do you ever feel that you are stupid or is it just other people? Or is that a stupid question?” I asked her.

“No, I can be stupid and I hate that even more! Because I… well… I know I’m bright and intelligent, so if I am stupid, it’s even worse!”

I asked for an example of her being stupid.

Prefer to watch instead?

“Well… I binge. Not often, now, but I waste money on food I’m just going to… well… sick up again. It’s so stupid.”

Sandy had been binge eating off and on for 25 years. She felt she had it under control, mostly, but still did it sometimes.

And her occasional all-or-nothing attitude to food carried over destructively to other parts of her life. Her mind was critical and her stupidity radar was set to high.

“If someone says the wrong thing, that’s it. I feel like I just don’t want anything to do with them. Everybody gets one chance and if they blow it, that’s it.”

“So, in another life, you could have been a fascist dictator?” I thought. But outwardly, I just looked at her and nodded encouragingly – the therapist’s default setting.

As if she’d heard my thoughts: “People often find me intimidating!”

“No kidding!” (again, without actually speaking).

Though you might not immediately turn to Sandy for some friendly support, I could see she was a tortured soul. And in there – like a small fragile flame of flickering light from a candle in a faraway place in the deepest of darkest nights – was her humanity. I could see it… just.

It’s lonely being perfect, especially when you’re not

Sandy was lonely. Other people irritated her, yes, but she also irritated herself.

Friendships and budding relationships had evaporated over the years, usually because other people couldn’t stand the bite of her judgment and unforgiving standards. Or she quickly found people’s imperfections not a sign of their humanity but of their wilful idiocy and rejected them.

But Sandy didn’t come to see me because she wanted help with perfectionism. She was sick and tired of being alone, wanted to feel less anxious, and needed to finally escape her occasional bulimic pattern once and for all.

She needed people, but pushed them away. She was borderline depressed much of the time, pessimistic, cynical, and unfulfilled in her career as a book illustrator.

What’s wrong with having high standards?

Being solution-focussed and driven can have us achieving wonderful things, of course. But for Sandy and many others, this approach gets so over-applied that it actually starts to block achievement and enjoyment of life.

Sandy had always learned fast, but, while still a child, had ripped up her music sheets when her piano practise didn’t go as she’d planned. Even though she’d shown great promise and been the best in her class, she decided piano was not for her and never went back to it.

This wasn’t so strange. It was perfectly(!) in line with the family ideology. Her parents valued achievement and being ‘the best’ at everything. If you weren’t the best, move on. And they passed these attitudes on to their children, including Sandy.

Nowadays she struggled to scrape by with occasional illustration commissions, but still would sometimes destroy an illustration she’d been working on for “reasons other people probably couldn’t even see”.

“My life has been full of false starts. If something is wrong or doesn’t fit how I think it should be, I tend to give up on it. I’ve had so many opportunities I should have pursued. I’ve stopped even trying to do stuff I feel may be hard or that I won’t be good at.”

Sandy needed to relax her standards so she could achieve more, because perfectionism was ruining her life.

The tyranny of perfectionism

Researchers have found evidence that perfectionism may be linked to the onset of eating disorders, such as bulimia and anorexia (1,2).

And I suspect that the extremist and emotional thinking of maladaptive perfectionism can also contribute to the onset and maintenance of some depressions. Depressive thinking tends to be all-or-nothing, black-and-white, and pretty unforgiving, especially of the self.

I worked long and hard with Sandy, hypnotically, seeking to unhook the residual bulimic ‘trance’ that still caught her out sometimes and to improve her stress management. We also looked at building her social and relationship skills and I used metaphor with her to develop an appreciation of others above and beyond what they were good at. We looked at the inherent value of things.

Here are three of the ways I helped her go from extremist intolerant to fair and humane in her attitudes to herself and others.

1) Describe the pattern

Sandy is an analytical thinker and likes to know why she is even talking about something.

I described how conditioning, personality, inflexible thought, and all-or-nothing thinking drive strong emotion. (After all, Hitler didn’t tend to talk in shades of grey in the Nuremberg rallies.)

I told her about Dr Martin Seligman’s research on how learning to challenge all-or-nothing thinking helped children who were at risk of becoming depressed avoid depression (3).

I also asked Sandy to imagine a world in which no mistakes were ever made, everything was always done entirely correctly, and skills were picked up instantly. She hypnotically envisaged this ‘perfect world’ for half an hour. When I asked her what it felt like, she said, “It’s cold… there’s no humour or fun… no satisfaction from having overcome adversity or challenge – it’s Hell!”

Chronic perfectionism is always a case of under-perceiving reality, what’s been called ‘straight line thinking’. We needed to deal with this.

2) Encourage a wider context

If we consider experiences in too narrow a context, we miss much of the fine detail of life.

For example, playing a friendly game with relatives at Christmas or some other get-together is:

- A chance to have fun, be creative, laugh, and bond with significant people in your life

- A chance to help other people feel good when they win

- A way of communicating with loved ones

- An opportunity to be creatively stretched regardless of who wins.

But a chronic perfectionist may miss all these wider contextual elements. When I asked Sandy what ‘the point’ of a competition, any competition, was, she immediately replied with: “To win, of course!”

It was a genuine revelation for her when we explored other possible purposes or by-products of a competition and she was intrigued to read new ideas on caetextia or ‘context blindness’. She had always thought, “What’s the point of going for a walk?” unless it was to exercise or actually get someplace. “What’s the point?” was her standard response to any idea or suggestion. What’s-the-point-ism is often a sign that someone’s thinking is too straight line.

Overcoming perfectionism sharpens perception and makes it more flexible and context aware, while also increasing humanity (to oneself and others).

3) Encourage downtime

All-or-nothing, black-and-white perfectionistic thinking is depressing. It’s tiring to be on such high alert all the time with perfectionism producing high levels of emotion and churned up feelings. And life can feel meaningless unless it’s ‘results driven’. So even the time after a successful endeavour can feel depressing.

Any ‘free time’ is not valued or tolerated in this repressive psychological regime.

Sandy’s life, if we saw it as a landscape, would have been full of sharp edges and sudden precipitous drops with towering mountain peaks. What she needed was a few places of respite – some comfortable, flat bits on which to rest and not feel like she had to be running ultra marathons (a hobby of hers), manically cleaning her apartment, or dieting.

I told Sandy that I wanted her to succeed at failing. I talked about humanity to her. I talked about being ‘human’ and ‘humane’ and how becoming comfortable with failure is the first step to success, social or any other. She needed downtime from having to be seen as perfect and ‘the best’ all the time.

I asked her to meet up with a friend she hadn’t seen for a while, a woman who had stayed friendly across the years. And she was to tell this friend a story of how she, Sandy, had ‘failed’ in some small way.

At the next session, she told me she had done just this. She met up with her friend and told her how she, Sandy, had joined MENSA a few years ago and had arrived a day early to their first social event. At the time, Sandy had been mortified, but while telling her friend about this episode, something weird suddenly began to happen. Sandy relaxed and they both laughed at the irony.

“In the end, we were both crying with laughter. It was wonderful. And, you know, I had to carry out your task, Mark, because if I hadn’t admitted to a failure, I would have failed the task!” (A classic therapeutic double bind.)

I kept asking Sandy to make small mistakes, practise laughing about them, and tell others of them later. People seemed to like her more as they found they could relax with her. She got more work, started another business, and was, in her words, “prepared to happily fail”. And she eventually found someone to love and be loved by.

The distant fragile candle flame became a beam of sunny warmth as the real Sandy released herself from the self-imposed repressive regime and into the light of day.

Notes:

- Hewitt, P.L., Flett, G.L., Ediger, E. (1995). Perfectionism Traits and Perfectionistic Self-Presentation in Eating Disorder Attitudes, Characteristics, and Symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 18(4). 317-326. DOI: 10.1.1.458.8328.

- Sutandar-Pinnock, K., Woodside, D.B., Carter, J.C., Olmsted, M.P., and Kaplan, A.S. (2003). Perfectionism in Anorexia Nervosa: A 6-24-month follow-up study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33(2). 225-229. DOI: 10.1002/eat.10127.

- See: Seligman, M. (2006). Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life.