Dig beneath the mystique of Milton Erickson’s case histories and the principles are simple enough for any therapist to learn and use.

“Sometimes – in fact more times than is realized – therapy can be firmly established on a sound basis only by the utilization of silly, absurd, irrational and contradictory statements.”

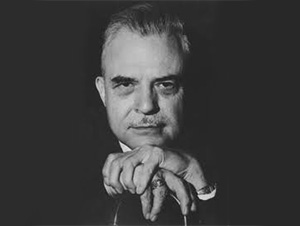

– Dr Milton H Erickson

In my last piece on Milton Erickson I suggested that what really made Erickson so effective at lifting people’s pain was his use of timeless principles.

Calling this ‘Ericksonian hypnosis’ is in a way misleading.

Prefer to watch instead?

Holding up a lone genius as an exemplar might be a very human tendency, but it’s a tendency that can hold us back from personal development.

‘Ericksonian’ principles have been known about for thousands of years.

Take the following ancient Sufi story, for instance. Don’t you think it clearly demonstrates the basic therapeutic principle of emotional utilization?

The physician and the paralyzed king

A powerful king was overtaken by a strange illness that rendered him paralysed. The king sent for a famous healer to come and cure him. This physician, however, refused to come. Enraged, the king ordered his soldiers to bind the physician and bring him forcibly to the royal chambers. “You are here,” declared the imperious monarch from his pillow, “because I’m suffering from a strange paralysis. If you cure me, you’ll receive a great reward. If you do not cure me, I will kill you!”

The physician, showing not a trace of fear, replied, “To be able to treat you, my Lord, I must have complete privacy.” So the king ordered all the servants and soldiers to leave the room. No sooner were they alone than the physician whipped out a sharp knife and said, “Now I’ll have my revenge on you for your threatening me!” As he stepped forward towards the bed where the king lay, the now terrified monarch jumped up and ran round the room, completely forgetting his paralysis in his need to escape this crazed physician.

Thus the king was cured in the last way he would have expected. Perhaps in the only possible way. Wisely, the doctor did not wait to be thanked, but fled the palace just ahead of the guards, and went into hiding in the neighbouring kingdom. The king eventually realized that perhaps he ought to reward rather than punish the man who had saved him, and months later pardoned the physician, allowing him to return to the kingdom. (1)

Milton Erickson and the paralyzed man

A woman in California wrote to Milton Erickson that her husband was totally paralyzed as the result of a stroke and could not talk. She asked if she could bring him to Erickson for help. Dr Erickson found the letter so pitiful that he agreed, thinking he might be able to comfort the woman enough to allow her to accept her difficult situation.

She brought her husband to Phoenix, registered at a motel, and came with him to see Erickson, who had his two sons carry the man into the house. Erickson took the woman into his office. She told him that her husband, a man in his fifties, had had this stroke a year before, and for the whole of that year he had been lying helpless in a ward bed in a university hospital.

The staff would point out to students, in the man’s presence, that he was a terminal case, completely paralyzed, unable to talk, and all that could be done was to maintain his health until he eventually died.

Why Erickson started insulting his therapy client

The man’s wife described her husband as a “a Prussian German, a very proud man. He built up a business by himself. He’s always been an active man and an omnivorous reader. All his life he’s been an extremely domineering man. Now I’ve had to see him lying there helpless for a year, being fed, being washed, being talked about like a child.” Erickson described the situation in his case notes:

As she talked, I realized that I need not merely comfort the woman; something might be done with the man. As I thought it over, here was a Prussian, short-tempered, domineering, highly intelligent, very competent. He had stayed alive with a furious anger for a year …

Erickson sat down in front of the man, who was unable to move anything but his eyelids. Then Erickson began his therapy:

“So you’re a Prussian German. The stupid, God damn Nazis! How incredibly stupid, conceited, ignorant, and animal-like Prussian Germans are. They thought they owned the world, they destroyed their own country! What kind of epithets can you apply to those horrible animals?”

Erickson continued to insult the man (and in even worse ways than just described) calling him lazy, and happy to lie about feeding off other people’s charity. Erickson then said that he hadn’t even had time to think of all the insults the man deserved, and he was to come back tomorrow to hear what Erickson really thought.

“And you’re going to come back, aren’t you!”

The man came back right then with an explosive “No!”

I said, “So, for a year you haven’t talked. Now all I had to do was call you a dirty Nazi pig, and you start talking. You’re going to come back here tomorrow and get the real description of yourself!”

He said, “No, no, no!”

I don’t know how he did it, but he managed to get to his feet. He knocked his wife to one side and staggered out of the office. She started to rush after him, but I stopped her. I said, “Sit down, the worst he can do is crash to the floor. If he can stagger out to the car, that’s exactly what we want.”

He lurched out of the house, even down the steps, and he managed to crawl into the car. My sons were watching him, ready to run to his aid.

After about two months the man was ready to return to California. He limped badly, had circumscribed use of his arm, and some aphasic speech, and he could read books but only if he held the book far to the side.

Erickson asked the man what he thought had helped him. He replied:

“My wife brought me to you for hypnosis. I always had the feeling after that first day when you got me angry, you were hypnotizing me and making me do each thing that I succeeded in doing. But I’ll take credit myself for walking fifteen miles one day in the Tucson zoo. I was very tired afterwards, but I did it.”

Holy Moses! What was that all about?

Knowing what motivates

Any decent therapy school will teach its students the principle of utilization, but the intuition of how to use utilization needs to be developed. This comes closer to our sense of wisdom than carefully planned therapeutic strategy, important though that may be.

Neither the physician in the ancient tale nor Erickson himself used what we would recognize as psychotherapeutic technique, but relied instead on an intuition based on clear perception of the personalities and drivers of these men. Sometimes you need perception – and courage – to truly help someone.

But surely this is ‘wrong’?

The art of suspending judgement

Many of us have been conditioned to instantly accept or reject something in simplistic ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ terms. This is a form of social conditioning that is effective for some things in life.

Is this correct? Have I been offended? Are my prejudices confirmed, and if not who’s to blame?

But sometimes this instant opinion forming can block creative opportunities for learning about something that might just contain an important truth that we need to know. Young children with their uncluttered perceptions haven’t yet learned to think like that, so reality can be more immediately available to them.

If we can bypass that learned reaction, that habit of instantly approving/ disapproving/ accepting/rejecting (reinforced as it is by YouTube and Facebook ‘likes’ and ‘dislikes’), we might be able, for a little while at least, to neither accept nor reject, believe or disbelieve, like or dislike, but instead to look, think, examine and experience.

Bypassing the yes/no like/dislike response and suspending judgement and prejudice can make us better learners in certain situations. Because what’s true or ‘good’ might not always look like it’s ‘supposed’ to look.

Understanding trance and motivation

If you understand hypnosis you’ll know that both the physician from the tale and Milton Erickson used emotion to hypnotize these men into a narrowed focus that brought about their healing. But to someone with only a restricted or rigid idea of how healing (or hypnosis) must happen, this might be hard to credit.

The story of the king, many hundreds of years old, prefigures the life-imitating-art Milton Erickson case (although it might itself, of course, have been based on a real event).

Both the king and the Prussian were haughty men, entitled to and used to powerfully exerting their own wills to control events. The physician uses the profound trance of fear as a motivator to have the king overcome his paralysis, while Erickson uses the trance of rage to help his patient talk and walk again.

I myself (not that I’m comparing myself to the physician or Erickson!) used the principle of the need to feel feminine to help a woman walk without her Zimmer frame.

Applying a principle is playing a role

So many therapists look to ‘technique’ in the hope that they can apply a one-size-fits-all approach to problems, but even with such universally effective approaches as the Rewind Technique we still need to take account of the unique motivations of individuals.

Once you have the principle, technique follows from it. Whenever we apply a principle, we play a role. The physician and Erickson were certainly playing a role, and so do you every time you sit with a client in a ‘therapeutic encounter’.

Someone reading this (not you, of course) might assume I’m suggesting that all paralysis is curable, or that it’s always necessary to use high drama to cure extreme conditions. Or that I’m condoning threatening people with knives or insulting vulnerable people.

I am not saying that at all.

Transcending technique

Principles may be the building blocks of technique, but when you have truly grasped the principles you can build your own technique that might seem strange from the ‘outside’.

The principles are timeless but a spontaneous technique might only ‘fit’ a single, very particular moment in time. People miss this when they assume that this is how Erickson ‘did therapy’, or this is how the physician from the story must ‘always’ have acted.

The ‘right thing to do’ in a particular set of circumstances may not look anything like the standard obvious (but perhaps short sighted) ‘right thing to do’.When people act from experience and intuition it might look ‘crazy’ from the outside.

Me flirting outrageously with an elderly lady in an old folks home is most certainly not the right thing to do… on paper. Not something I’d ever done before, or am ever likely to do again (until, perhaps, such time as I’m actually in an old folks’ home myself!). And I hope no school will ever teach that as a ‘technique’.

But the principles behind it are sound. Dig beneath the mystique of Milton Erickson’s case histories and the principles are all pretty simple.

I like to teach principles first, techniques second. Once you fully understand the principles, you find that the standard ‘technique’ can sometimes be helpfully transcended. A good hypnosis or psychotherapy school will never just teach you technique without giving you the means, the principles, to build technique.

No training provider worth their salt will ever suggest that you read scripts to your clients, because sometimes, in therapy as in life, we all need to go ‘off script’.

Notes:

1) See page 83 of Seeker After Truth by Idries Shah for a slightly different telling of this tale used by Sufis to illustrate truths as part of their spiritual and psychological training and a way to challenge restricted thinking.